1. Forced Appearances in Adult Pornographic Videos (AV)

Damage to Young Women

In Japan, it has been frequently reported that many young women who were scouted as TV personalities or models were tricked or pressured into performing in adult pornographic videos (AV). In many cases, these young women signed agency contracts without knowing what would happen. The victims realized that they would be in a pornographic video only after being sent to a shooting location, and were told that they would have to pay a penalty if they refused the work.

Forced appearances in AV cause serious damage to victims, including physical and psychological harms. Not only are the victims forced to have “sexual intercourse” in the name of contract, but once the video is released, it continues to spread indefinitely on the internet. That causes suffering to women for a significant amount of time. As a result, the victims often suffer from PTSD, or in some cases, commit suicide.

Our Report

In 2016, Human Rights Now (HRN) released an investigative report on the damage of forced appearances in adult pornographic videos, which resulted in a strong public reaction.

In March 2017, the Japanese government embarked on enacting damage prevention measures that focused on public awareness raising, but without regulatory agencies, laws, or regulations, the situation remained unchanged. Under these circumstances, HRN continued to sound alarm and raise social awareness on the issue in collaboration with victims of forced appearances in AV and victim support organizations.

Call for Legislative Action

The major turning point came in April 2022, when the legal age of adulthood in Japan was lowered from 20 to 18-years-old. Before the change was made, any contracts made between an actor/actress under 20-years-old and a film production agency could be canceled under law. However, beginning on April 1, 2022, the law no longer protects the right of people 18 years of age and older to cancel contracts once they are signed. In order to prevent further damage to young people, it has become necessary to call for a bill that allows 18- and 19-year-olds to cancel contracts for appearing in adult videos that they signed against their will.

On March 15, 2022, HRN submitted a written request to political parties in Japan. On March 23, 2022, HRN and PAPS co-hosted an emergency rally in the National Diet building to urge Diet members to propose a bill that allows 18- and 19-year-olds to cancel contracts for appearing in pornographic videos that they signed against their will. The rally was widely covered by the media.

As discussions in the National Diet progressed in the following month, discussions between the ruling and opposition parties on the bill also began. On May 9, 2022, HRN and victim support organizations were invited to a hearing in the National Diet building. Along with five other organizations, HRN attended and submitted a written request and a joint written request to the hearing.

From Bill to Law

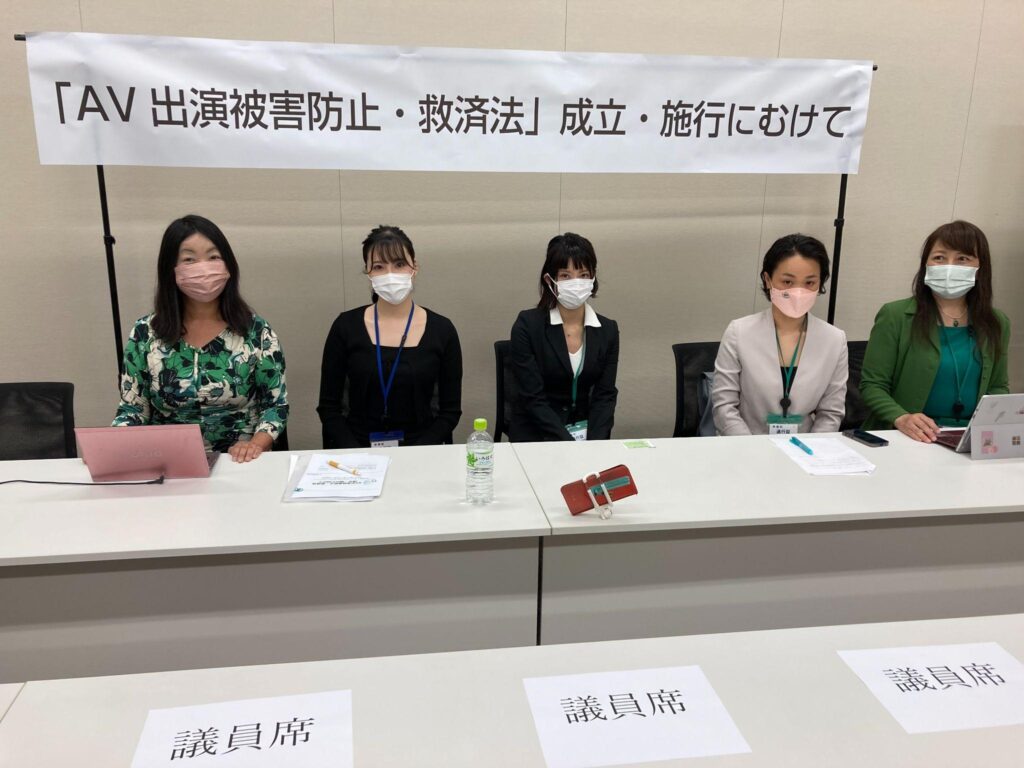

On May 27, 2022, “The Adult Video Appearance Damage Prevention and Relief Bill” was unanimously adopted by the House of Representatives, and on June 15, 2022, it was adopted by the overwhelming majority of the House of Councilors and passed into law. On the same day, HRN held a press conference in the National Diet building along with PAPS and SPRING, victim support organizations, and Kurumin Aroma, a social activist/YouTuber/former actress. The new law entered into force on June 27, 2022.

(Press conference on June 15, 2022)

Future Challenges

In order to relieve extremely serious damage that had not been exposed to light, it is necessary to immediately establish an implementation system for the new law and promote the establishment of a damage relief system. Making this law available and easily accessible to victims is another important task. It is necessary to establish counseling agencies that are easy to consult, disseminate information to related organizations, hold consultations and training, and above all, enhance public relations and outreach to those who need this law.

As an organization that played a central role in the advocacy of the new law, HRN will continue to ensure that it is properly implemented and damage relief is realized. We will continue to make our efforts to ensure that positive revisions will be considered in the review that is stipulated within two years from now.

2. Digital/Online Sexual Violence

In recent years, damage has been caused to victims by so-called “Digital sexual violence,” which typically consists of filming unconsented sexual acts or forcing victims to do sexual acts by threatening to distribute the filmed images to others. Therefore, it is necessary to establish provisions to punish unconsented filming.

To address these issues, HRN submitted a comprehensive legislative proposal titled “Request for the Establishment of a New Crime Related to the Photographing of Sexual Desire, etc.” on February 24, 2022 to political parties in Japan. In addition, HRN investigated legislations or policies of different countries to punish digital sexual violence and submitted an investigative report to the Legislative Council on April 27, 2022.

Although there is currently no definition of “Digital sexual violence” in the Japanese legal system, our report defines it as “the act of using a computer, smartphone, camera, or other electronic devices to photograph a person in a sexual manner without the person’s consent; distributing the actual video, etc.; using the photographed or created sexual images to harass, stalk, threaten, or otherwise cause emotional distress to the person; and forcing the person to send sexual selfies.“

2023 Revision of the Penal Code

On June 16, 2023, the Japanese Parliament passed a law that will significantly transform the country’s sex crime laws. The law’s primary aims are to broaden the definition of the punishable crime of forced sexual intercourse and bring Japan closer to international rape legislation standards. Hence, the penal code has been amended in the following ways:

- The age of consent has been raised from 13 to 16 years.

- The definition of rape was broadened to “nonconsensual sexual intercourse” from “forcible sexual intercourse”, aligning Japanese law’s definition with other countries.

- The rigid requirements that establish the crime of nonconsensual sex have been expanded to include cases in which physical coercion or violence is absent. The new law takes into account various factors that can lead to a victim’s non-consent, such as power imbalances, societal or financial standing, “freezing” responses, alcohol or drug use, or a victim’s possible mental illness.

- New crimes have been established combatting so-called “upskirting” or the non-consensual sharing of intimate images.

- The statute of limitations for nonconsensual intercourse has been raised from 10 to 15 years. In cases of sexual assault resulting in injury or death, the statute has been raised from 15 to 20 years.

Human Rights Now (HRN) strongly welcomes these changes, as HRN has been consistently involved with advocacy work regarding the revision of the penal code since 2017. Several amendments to the law have been championed by HRN and other advocacy groups (e.g., Spring) for many years. HRN has continuously made policy proposals to the Japanese government and released an extensive and timely report concerning the penal code revisions. (Read here). The revised penal code comes closer to orienting around victims and their real-life experience, hopefully making it easier for survivors of sexual assault to find justice.

Despite this progress, there are still challenges that remain. HRN has repeatedly called for Japanese legislators to abolish conditions to the sexual crimes penal code that are too difficult for victims to prove. However, the current requirements to establish the crime of rape still include some burdensome conditions for victims. Specifically, the second condition (proof that non-consensual intercourse was “significantly difficult to reject) presents a significant hurdle for victims that want to pursue legal action. Additionally, Japanese legislators still do not clearly state that all nonconsensual intercourse is rape anywhere in the renewed penal code. Considering these shortcomings regarding its content and wording, HRN retains that Japan’s sexual crimes penal code still has some way to go regarding meeting international rape legislation standards.

The most important change in the law pertaining to nonconsensual pornography is the establishment of new crimes combatting so-called “upskirting” or the nonconsensual sharing of intimate images. The act of secretly photographing or filming a person’s sexual anatomy and providing such photos or videos to a third person is now punishable under the newly introduced law. Perpetrators of such crimes may be imprisoned for up to three years or need to pay a minimum of ¥3 million ($21,170) in damages. The creation of these crimes marks a significant step toward preventing the creation and sharing of nonconsensual pornography. As HRN has been actively involved in advocacy work regarding the creation and distribution of nonconsensual pornography, the establishment of these new crimes is a highly welcomed development. However, there are still several remaining challenges in this context as well. Mainly, these challenges are related to “digital sexual violence”. Lawmakers need to to start focusing on technology-based sexual abuse related to AI and deepfake technology in order to address the full spectrum of possible sexual crimes. Moreover, in order to effectively prevent all manifestations of digital sexual violence, it is imperative that domestic laws hold social media platforms accountable as they serve as the primary channels for the distribution of nonconsensual pornography.

Best practices from around the world

In our efforts to end all forms of digital sexual violence, HRN works closely together with international NGOs and experts to compile best practices and possible legal solutions. Firstly, lawmakers must focus on monitoring and regulating social media companies and their approaches to digital sexual violence, particularly when it comes to revenge porn or deceptive advertisements for the porn industry. International experts call for a “safety by design” approach to social media platforms. When platforms are designing their service, they are responsible for implementing proper risk assessment and content mediation. For instance, platforms could have a system whereby users who want to share pornographic images should at least be identifiable by the platform so that if the images turn out to be a problem, there is a way of tracking the perpetrator. Furthermore, terms and services could ban specific uses of social media platforms, such as deceptive advertisements for the porn industry. Governments could mandate such practices, as many social media platforms resist such measures. Secondly, it is essential that lawmakers design laws with as few barriers to victims as possible. Often, definitions for sexual crimes are too narrow for a criminal offense to be established, making it difficult for victims of digital sexual crimes to come forward. Finally, many states worldwide have experienced the skyrocketing of non-consensual explicit image sharing, making clear the necessity to improve local community support and services that support victims.

Recommendations for Japanese lawmakers

- Strengthen the duty of the government by establishing a supervising authority to enforce the new Act and a one-stop victim support center to eliminate images and videos, such as the one-stop victim support center used in South Korea

- Impose binding duties on relevant industries, such as platforms, service providers, and Big Tech companies, beyond the non-binding UN Guiding Principle on Business and Human Rights

- Tackle transnational cases of forced appearances in adult pornographic videos

- Further develop the Act to recognize the right to be forgotten, expand sanctions, and determine whether a certain activity should be regulated or prohibited

- Continue working on the issue of digital sexual abuse to protect victims online

- Target social media platforms as subjects for new laws