Human Rights Now (HRN), a Tokyo-based international human rights NGO, surveyed seven general trading companies regarding their human rights policies and practices (Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsui & Co., Itochu Corporation, Sumitomo Corporation, Marubeni Corporation, Sojitz Corporation, and Toyota Tsusho Corporation). Based on the results, HRN released a report in Japanese on trading companies’ human rights initiatives, “Japanese Trading Companies: Measures for Human Rights Lag Far Behind International Standards”, which it released at a press conference at the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Press Club on 13 February 2020. On 12 March 2020, HRN released the English translation of this report.

The English version of the report is printed below and is available in pdf format from the following link: Japanese Trading Companies: Measures for Human Rights Lag Far Behind International Standards.

The English translation of the survey questions are available in pdf format from the following link: Survey Questions for Japanese Trading Companies.

The survey results of two companies, Mitsubishi and Sojitz, included English translations by the companies. They are available from the following links. (1) Mitsubishi Corp. Survey Response, (2) Sojitz Corp. Survey Response.

The other companies’ responses were only in Japanese and are available on our Japanese website from the following link, along with the Japanese version of the report and the recommended guidelines mentioned in the report (also in Japanese): https://hrn.or.jp/news/17225/.

Executive Summary

The report concludes that the majority of the companies’ efforts, in terms of implementing an effective human rights due diligence system including supplier audits, have been insufficient, and lag far behind international human rights standards as required by the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP). Much room for improvement remains. In particular, there remain many problems in ensuring respect for human rights in supply chains, regardless of the industry. Effective auditing systems and human rights due diligence systems have been established in only a handful of cases, and there is a significant gap between published human rights guidelines and their implementation (systems for which remain lacking). If an effective auditing system and human rights due diligence system are in the process of being established, the process should be disclosed for the purposes of accountability. Despite this, most of the companies have not implemented adequate measures in terms of transparency and information disclosure.

The report ends with several recommendations to the companies including developing a human rights policy in line with the UNGP, sharing it with suppliers and business partners and working with them to properly implement it, conducting human rights due diligence and audits throughout supply chains, conducting more dialog with stakeholders, and establishing accessible grievance mechanisms.

Japanese Trading Companies: Measures for Human Rights Lag Far Behind International Standards

In the summer of 2019, Human Rights Now, a Tokyo-based international human rights NGO, conducted a survey on human rights policies and related company efforts of seven general trading companies in Japan (Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsui & Co., Itochu Corporation, Sumitomo Corporation, Marubeni Corporation, Sojitz Corporation, and Toyota Tsusho Corporation). HRN received responses from all of these trading companies.

Given in particular the grave human rights issues throughout global supply chains, the role of trading companies that procure a wide variety of goods from all over the world, such as clothing, food, timber, mineral resources, and energy, is extremely important.

There are strong expectations for trading companies to undertake fundamental reviews of their human rights measures and to formulate and implement policies based on the United Nations “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights” (“UNGP”), endorsed by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2011.

However, the answers to this survey indicate that while the trading companies are aware of the need to address human rights issues, the concrete systems and measures to realize this responsibility remain insufficient, and the need for improvement is extremely high.

- Human Rights Policy

The importance of establishing and implementing a human rights policy is pointed out in the UNGP, as it establishes a clear commitment to respect human rights both internally and to parties outside of the company.

In this regard, six out of the seven companies responded that they had established human rights policies. The one that responded they had not done so, Sumitomo, is a signatory to the 10 Principles of the United Nations Global Compact, and as such it is urgently required to adopt a human rights policy that demonstrates its commitment to human rights.

Companies’ human rights policies are required to specify the international human rights standards upon which their business activities are based. In this regard, while all companies other than Toyota Tsusho Corporation (“Toyota Tsusho”) explicitly state that they are in compliance with international human rights standards, only Sojitz Corporation (“Sojitz”), Marubeni Corporation (“Marubeni”), and ITOCHU Corporation (“Itochu”) have explicitly stated what measures they would take if international human rights standards and national standards are in conflict. It should be noted that, as in the past, a company’s compliance with domestic laws alone is not sufficient for it to meet its responsibility to respect human rights as required by the UNGP. It is even more important that a company take into consideration how it acts in such cases. In addition, it is expected that companies make specific commitments that go beyond standard language, such as referring to specific human rights that are particularly relevant to their respective sector.

It is also imperative that human rights policies are promoted throughout the company, through measures such as internal training and fully embedding them into daily business activities.

The responses indicated that e-learning is likely to be provided for new employees and executives. However, there is room for improvement in the way the policies are disseminated from the viewpoint of the effectiveness of such training, and the extent to which it has an impact.

In particular, it is crucial that companies take seriously the need to ensure employees understand the UNGP. For instance, the seminar organized by Itochu inviting external experts on Business and Human Rights, including civil society, may be evaluated as positive insofar as it could promote a dialogue between civil society. The formulation of a human rights policy is just the first step, and it is expected that the policy will serve as a foundation for establishing a system for implementing business activities in accordance with the policy.

- Encouraging suppliers to protect human rights

It is positive that all seven companies require their suppliers to respect human rights through their codes of conduct. For example, in fiscal 2013, Itochu answered that they had sent their code of conduct to 4,000 companies with which they had ongoing business transactions, and from 2015, it has become obligatory to notify new suppliers. However, the sharing of the code of conduct is not sufficient to prevent or mitigate human rights risks.

Only MITSUI & CO., LTD. (“Mitsui”), Mitsubishi Corporation (“Mitsubishi”) and Itochu regularly audit their suppliers. Among them, Itochu and Mitsui replied that they conduct third-party audits. However, it is not clear from the responses whether these three companies regularly audit just the direct suppliers of the materials they handle, or also the upstream suppliers up to the country of origin of the raw materials.

Mitsubishi states on their website that “In order to ensure that the principles outlined in our Policy for Sustainable Supply Chain Management are being upheld in our supply chains, we conduct regular surveys of our suppliers that operate in higher risk industries such as agriculture and apparel”;[1] however, there is information on only one on-site audit in fiscal 2018. As for surveys, Mitsubishi also reported having received responses from approximately 300 companies in approximately 30 countries and regions in 2018, but it is obvious that this does not cover all of its suppliers.

Itochu states on their website that “in order to check the status of our various suppliers, each of the Division Companies and relevant Group companies of Itochu selects significant suppliers based on such parameters as high-risk countries, products handled and transaction amounts”, and it conducts sustainability surveys by providing questionnaires. It also mentions that on-site surveys are conducted “as necessary”, which means on-site audits are limited, although they state that for food products they conduct regular visits to food processing plants of overseas suppliers.[2]

Mitsui said that it had conducted supplier surveys since 2015, including on-site inspections of manufacturing sites. However, the publicly available information indicates that such inspections are conducted only at one place per year, and that the products covered are limited to food products.[3]

Marubeni, on the other hand, responded that it was in the process of establishing a comprehensive investigation system, and the remaining three companies reported auditing only when deemed necessary. Thus, it cannot be said that these companies have a sufficient governance system to ensure that they fulfill their human rights policies in their supply chains. Under the current circumstances, human rights violations may not be addressed until they have escalated to the level that they are evident to the companies.

On the other hand, Sojitz’s approach to wood procurement is commendable: “Sojitz also has adopted use of WWF Japanʼs ‘Responsible Purchasing Checklist for Forest Products’ to confirm 1) wood traceability in the countryof origin and 2) suitability of forest management with referring to advices fromWWF Japan” (sic).

Overall, there are serious concerns from the survey that, even if the companies have human rights policies, their efforts are still limited to wishful thinking, leaving severe human rights violations overlooked.

Questionnaires are one of the most commonly used methods for investigating human rights violations, but they are only partially implemented, and violations are not detected if suppliers do not provide honest answers about them. Only a handful of companies have conducted on-site inspections.

The lack of disclosed information on supply chain issues related to minerals, resources, and energy (electricity, oil, coal-fired, and natural gas), all of which are prone to serious human rights violations, is a growing concern, in addition to the limited number of initiatives in some reported cases, such as in the food, textiles, timber, and palm oil sectors.

In order to prevent, mitigate, and remedy human rights violations based on the UNGP, it is necessary that companies conduct regular and effective audits of all commercial products and publicly disclose the results.

With regard to human rights due diligence in supply chains, Sumitomo responded that it remains unconducted, while Marubeni answered that it was in the process of establishing a system. Sojitz was the only company in the survey that reported conducting human rights due diligence, and the remaining four companies reported conducting it partially. Out of those four, Itochu stated it carried out human rights due diligence on “Companies in high-risk countries with transactions exceeding a certain amount,” which comprise 8% of all companies with which they have business. Mitsui responded that it conducted human rights due diligence only for “New business investment projects that have a significant impact on the environment and society”. Mitsubishi did not disclose any details regarding any human rights due diligence efforts.

A trading company is a unique type of business that operates its own group of companies and is involved in a wide range of industries around the world. This results in a high level of human rights risk. Therefore, comprehensive human rights due diligence across suppliers is indispensable.

In this regard, Sojitz states that it makes risk assessments based on the assumption “that even those trading businesses where transactions comprise small amounts or which carry a small profit margin can belong to supply chains where upstream development/production carries a significant impact on the environment and human rights.” Additionally, Sojitz says that “[i]n addition to our wood procurement-related initiatives, we will continue to gradually expand the scope of risk assessment to Sojtiz Group companies and suppliers according to priority.”[4] These positions are commendable.

Both human rights due diligence and audits are measures that can identify, prevent, mitigate, and remedy potential or actual human rights risks across supply chains and value chains.

The increase in the number of companies reporting on their supplier fact-finding surveys is a positive sign, in particular in that it involves direct communication with stakeholders, but the number of fact-finding investigations clearly remains small, and comprehensive, transparent audits are still required. It is critically important that companies disclose the human rights risks identified among their suppliers as a whole as well as their responses, so as to ensure accountability to stakeholders.

- Identifying suppliers and disclosing supplier lists

Sojitz, states that it has information of suppliers up to tier 3 and beyond. Sumitomo says that it has information of up to tier 3 suppliers, and Itochu says that it has information including some tier 2 suppliers. Sojitz has information on tier 1 suppliers of products other than timber. Also, Mitsui and Mitsubishi has information on tier 1 suppliers. Marubeni is now establishing a system. Toyota Tsusho did not respond on this point.

Given the need for companies to respect human rights in their supply chains, it is a considerable problem for a company to not be fully aware of its suppliers. Companies should make greater efforts to identify their suppliers in order to identify human rights risks, just as they make great efforts in assessing quality control of their suppliers.

In addition, none of the companies surveyed has disclosed their supplier lists. In recent years, an increasing number of companies have opened their supply chains to the public, as part of their responsibility to respect human rights.

The companies surely have a large number and variety of suppliers, due to the nature of trading companies. However, the UNGP emphasizes that it is the role of companies to identify human rights risks. Companies should disclose their supplier lists.

- Identification of the employment of Technical Intern Trainees and prevention of human rights violations against them

Mitsui and Sumitomo responded that their business partners, including suppliers, employ intern trainees, while the rest of the companies stated that they did not know. Technical intern trainees are in an extremely vulnerable position, with a high risk of human rights abuses. Various government reports and media have already shown the grave violations that occur against technical intern trainees, including deaths, disappearances, passport confiscations, and exploitative labor practices including pay under the minimum wage. It is of serious concern that trading companies have not taken any measures in this regard. They should immediately ascertain whether or not their suppliers are involved in such abuses and, if so, take appropriate measures.

- Diversity and prevention of discrimination and harassment

Although all of the companies stated they take measures to strengthen diversity, the ratio of females among management staff is extremely low. While 0% of Mitsubishi’s and Sojitz’s executive directors are female, Itochu has 4.5 %, and Toyota Tsusho has 2.9% according to their responses. The rest of the companies did not state the ratio.

Discrimination and harassment are frequent violations of workers’ rights, and it is crucial to prevent them. However, Sojitz was the only company that went beyond the guidelines to engage in specific activities.

Sumitomo did not take any measures to prevent discrimination or harassment within suppliers, at the time of its response. While Marubeni, Toyota Tsusho, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Itochu have established Codes of Conduct, there do not appear to be any measures taken to ensure their effectiveness. Those companies need to consider taking prompt action against human rights risks.

It is also an urgent task for companies to establish systems to prevent harassment internally, as some former trading company employees have reported being subject to sexual harassment while job hunting. It is necessary for them to investigate the situation, and to establish systems based on the “ILO Violence and Harassment Convention”.

- Living wages, child labor, and forced labor

According to the responses, Sumitomo has not taken any measures regarding the ensuring of living wages. Mitsui and Mitsubishi state they are addressing the issue, and Marubeni is establishing a survey system. Sojitz states, “At present, Sojitz strives to confirm and improve with priority given to ‘payment of minimum wage’.” Itochu and Toyota Tsusho have merely set goals of preventing unfair low-wage labor practices. It is not clear if Mitsui and Mitsubishi have taken concrete measures in this regard. Improving labor practices that violate human rights is an important international issue, so effective efforts must be taken.

With respect to child labor, forced labor, and human trafficking, although the responses differed for each company, it was not clear to what extent concrete measures have been implemented across supply chains.

It is welcomed that Mitsubishi and Itochu have conducted on-site inspections of the situation of migrant workers in their food industry supply chain in Thailand, in response to our organization’s report on the issue.

- Establishment of a grievance mechanism for the protection of human rights

All of the companies reported having a grievance mechanism for the protection of human rights except for Marubeni, which said it was currently establishing one. Operating grievance mechanisms in multiple languages (not only Japanese but also English and other languages) are necessary for accessibility. For example, Sojitz offers its grievance mechanism in 24 languages for its employees including group companies, as well as in Japanese and English for its external stakeholders. Toyota Tsusho offers one with 9 languages. However, only two companies, Itochu and Sojitz, have established grievance mechanisms that can be used by business partners including suppliers. Another critical issue is whether people at the very end of supply chains can access the system.

The UNGP calls for the establishment of grievance mechanisms not only through existing judicial institutions but also within companies in order to ensure access to remedies. This aims towards ensuring the voices of rights holders and also towards preventing human rights violations from worsening. Companies must immediately establish a remedy consistent with the UNGP, and make it accessible to broader stakeholders including workers in all supply chains of all goods.

- Stakeholder engagement

In human rights due diligence, since the implementing entity is the company itself, there is often the incentive to focus on risks to the company, as opposed to the risks of rights holders. However, the UNGP defines human rights due diligence as a process for preventing, mitigating, and remedying human rights violations of rights holders.

When considering human rights risks, it is essential to focus on rights holders who may be affected by business activities, such as workers and local residents. Stakeholder engagement is one of the means to ensure this perspective.

It is commendable that the surveyed companies have had dialogues with NGOs (excluding Toyota Tsusho) and local residents (excluding Sojitz). It is desirable that all dialogues be publicly disclosed, including not only the fact that the companies have had them, but also the human rights risks raised in them.

Business has a significant impact on the lives of local residents, especially socially vulnerable actors such as women, persons with disabilities, and children. Thus, companies should also ensure dialogues with such actors.

- Conclusion

It is positive that, since the adoption of the UNGP in 2011, efforts have been made by each of the seven major trading companies to strengthen their respective human rights measures, such as the formulation of human rights policies. Nevertheless, there remain many issues in investigating and disclosing human rights issues in supply chains. The majority of the companies’ efforts, in terms of implementing an effective human rights due diligence system including supplier audits, have been insufficient, and lag far behind international human rights standards as required by the UNGP. Much room for improvement remains. In particular, there remain many problems in ensuring respect for human rights in supply chains, regardless of the industry.

Effective auditing systems and human rights due diligence systems have been established in only a handful of cases, and there is a significant gap between published human rights guidelines and their implementation (systems for which remain lacking). If an effective auditing system and human rights due diligence system are in the process of being established, the process should be disclosed for the purposes of accountability. Despite this, most of the companies have not implemented adequate measures in terms of transparency and information disclosure.

Under these circumstances, there is a serious concern that procurement by trading companies are a “black box”, and that many human rights violations in the global supply chains related to Japanese businesses and consumers will continue without improvement.

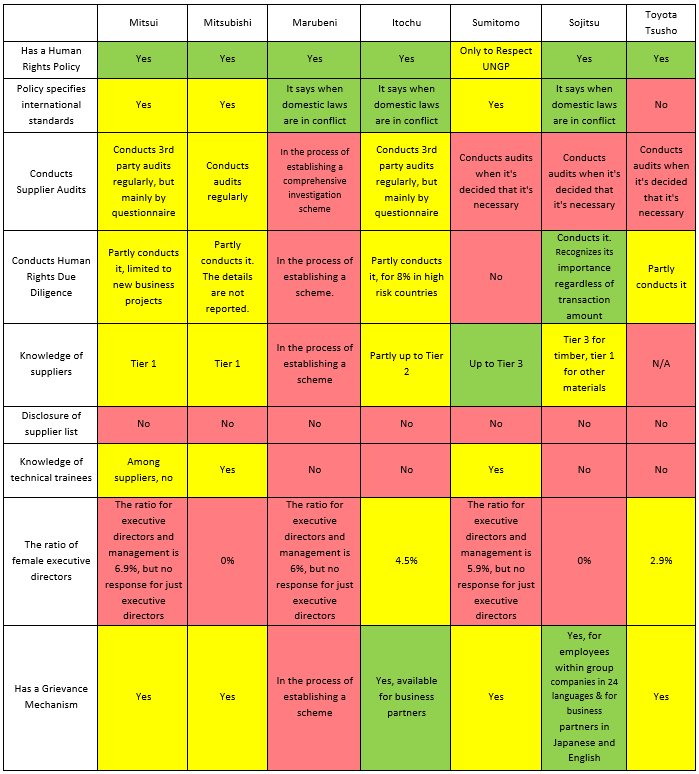

An overview of the responses we received from our survey follows below. Cells in green signify accordance with the UNGP to some extent; those in yellow mean measures are at a certain standard but there is room for improvement; and those in red require urgent action.

We request each company to recognize their responsibility to ensure the respect and protection of the human rights of workers and related stakeholders in their supply chains, and to demonstrate how it will achieve this in medium- to long-term management planning, including roadmaps and specific KPIs.

Regarding the SDGs, some companies have mapped their efforts by specific goals. However, SDGs are only guidelines, and excessive labeling of each goal departs somewhat from the true nature of the SDGs, which centers on the impact on people. Although often overlooked, paragraph 67 of “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” refers to the UNGP as the main principle for private sector engagement in the SDGs. In other words, it requires that all business activities comply with the UNGP when implementing initiatives to achieve each of the SDGs’ goals. We urge the companies to recognize this.

Human rights risks in business cannot be entirely eliminated, so long as corporate activities take place in connection with society and people. That is exactly why human rights risks must be identified at an early stage and remedies provided as a responsible corporate action.

We recommend referring to the appendix, which describes the human rights due diligence process which the OECD recommends as well as some good practices found among foreign companies. It shows the serous gap between Japanese companies and international trends.

If companies are slow to implement voluntary initiatives based on the UNGP, there is an increasing need to consider introducing legislation that requires human rights due diligence under specified conditions, such as in the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and the Netherlands, as well as legal systems that prohibit the import of goods for human rights violations, such as forced labor and child labor, such as the Trade Facilitation Act in the United States.

As a civil society organization, we will continue to engage in constructive dialogue to promote consumer awareness and, at the same time, accelerate collaboration toward the realization of a sustainable society.

Given the survey results, we, Human Rights Now, make the following requests again to each general trading company:

- Develop a human rights policy in line with the UNGP;

- Share the human rights policy with suppliers and business partners through dialogue, and work together to implement them;

- Promptly conduct human rights due diligence for the identification, prevention, and mitigation of human rights risks, and disclose the process, progress and challenges with due diligence and with identified human rights risks to ensure accountability;

- Identify suppliers up to the level of the procurement of raw materials and publish a list of suppliers;

- Conduct independent and effective periodic audits throughout the supply chains of all products and disclose the results;

- Immediately investigate whether technical intern trainees are involved in the company’s supply chains, publish the findings of the investigation, and establish a mechanism to prevent, mitigate, and remedy human rights violations;

- Identify human rights risks such as discrimination, harassment, forced labor, child labor, and human trafficking; establish mechanisms for the prevention, mitigation and remedy of such risks; at the same time work to achieve living wages; and fundamentally improve the gender ratio among executive directors;

- Implement continuous dialogue with stakeholders; and

- Build a grievance mechanism accessible to all stakeholders in the company’s supply chains.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.mitsubishicorp.com/jp/en/csr/management/supplychain.html

[2] https://www.itochu.co.jp/en/csr/supply_chain/management/index.html

[3] https://www.mitsui.com/jp/en/sustainability/sustainabilityreport/2019/pdf/en_sustainability_2019-38.pdf

[4] https://www.sojitz.com/en/csr/supply/; https://www.sojitz.com/en/csr/supply/lumber/

Note: updated March 16 to use Sojitz’s own English translations of its responses.